Working Stone (2009-2016)

Nearly half a billion years ago, Vermont lay under a warm, shallow sea. Prehistoric marine organisms, whose fossils are still visible on rocky outcrops, built reefs that over eons turned to limestone. Continents collided, mountains taller than the Himalayas rose, and under great pressure the marine limestone sediments on the western side of the state metamorphosed into marble. On the eastern side, igneous granite deposits formed from the slow crystallization of molten rock below the surface of the earth. Stone made from ancient undersea creatures and rocks of pressurized lava — these are the hallmarks of the geological and historical landscape.

In more recent years this stone has been quarried, first by Abenaki and other native tribes for tools, then by farmers who walled the land and built sturdy houses, then by industrialists who extracted huge blocks of marble and granite before abandoning one site and moving on to the next. In open quarries and underground caverns, workers removed stone. There are still active quarries in Vermont, although there are many more abandoned ones slowly succumbing to water and weather and time.

Many photographs in Working Stone explore the active quarries of Vermont, workplaces whose scale dwarfs the men and machines that remove massive blocks of rock, sometimes to be ground into mountains of small stones. Other photographs contemplate inactive sites, whose rock faces still bear traces of human interaction with the geologic landscape.

I am fascinated by the way the stone has been and is still worked — by the ladders, hoses, bolts, and derricks, by the trucks and saws and generators. But most of all, I am drawn to the stone itself, with its textures, colors, lines, and marks reading like a map of time stretching back beyond humanity.

1. Middlebury, VT

2. Rochester, VT

3. Middlebury, VT

4. Barre, VT

5. Danby, VT

6. Danby, VT

7. Rochester, VT

8 Barre, VT

9. West Rutland, VT

10. Proctor, VT

11. South Wallingford, VT

12. South Wallingford, VT

13. Danby, VT

14. Danby, VT

15. Danby, VT

16. Danby, VT

17. Barre, VT

18. Barre, VT

19. Barre, VT

20. West Rutland, VT

21. Barre, VT

22. Barre, VT

23. Middlebury, VT

24. West Rutland, VT

26. Proctor, VT

25. Rochester, VT

My Hard Hat!

Residential Installation

Working Stone at Redux

Working Stone on view at Redux Contemporary Art Center in Charleston

Working Stone at Redux

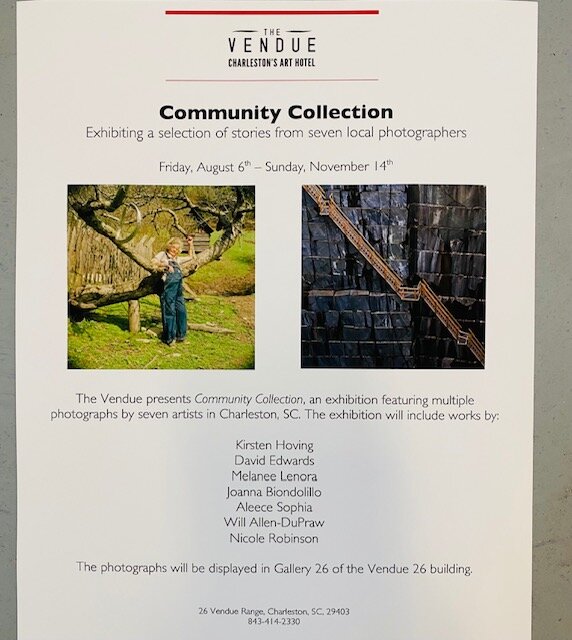

Selections from Working Stone at Gallery 26, The Vendue Hotel